C# Yield Return Demystified

One C# language feature that can initially seem like magic is yield return. This feature is very similar to generators in Python. Generators (in Python) and yield return (in C#) allow you to write very simple-looking functions to implement behavior that normally would require more complex stateful iterator objects. This post will explain the behavior of a function using yield return and then explain what code would be required to implement this behavior without yield return.

Implementing IEnumerable with yield return

Here is an example of a function that uses yield return:

IEnumerable<string> YieldReturnDemo(int first, int last)

{

var beginTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

yield return $"begin";

for (var i = first; i <= last; i++)

{

yield return $"item {i}";

}

var endTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

yield return $"end ({(endTime-beginTime).Duration()} since begin)";

}

As you can see this function returns an IEnumerable<string> which means it can be used in a foreach loop like this:

foreach (var s in YieldReturnDemo(2, 8))

{

Console.WriteLine(s);

}

Running this will produce the following output:

begin

item 2

item 3

item 4

item 5

item 6

item 7

item 8

end (00:00:00.0002520 since begin)

Pausing and Resuming at yield return

The thing that is interesting about this is the strings above are not built up into a collection in memory and then iterated over, each item is produced only when it is needed. When the yield return is encountered the function effectively pauses and the value from the yield return statement is produced as the next value in the enumeration. Later, when the loop asks for the following value, the function resumes and runs until the following yield return is encountered.

To prove that the function is paused and resumed like this you can add Console.WriteLine statements to the function like this to help demonstrate the order of execution:

foreach (var s in YieldReturnDemo(2, 8))

{

Console.WriteLine(s);

}

IEnumerable<string> YieldReturnDemo(int first, int last)

{

var beginTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

Console.WriteLine("--Before Begin");

yield return $"begin";

Console.WriteLine("--After Begin");

for (var i = first; i <= last; i++)

{

Console.WriteLine("--Top Of Loop Body");

yield return $"item {i}";

Console.WriteLine("--Bottom Of Loop Body");

}

Console.WriteLine("--Before End");

var endTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

yield return $"end ({(endTime-beginTime).Duration()} since begin)";

Console.WriteLine("--After End");

}

This will produce the following output:

--Before Begin

begin

--After Begin

--Top Of Loop Body

item 2

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Top Of Loop Body

item 3

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Top Of Loop Body

item 4

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Top Of Loop Body

item 5

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Top Of Loop Body

item 6

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Top Of Loop Body

item 7

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Top Of Loop Body

item 8

--Bottom Of Loop Body

--Before End

end (00:00:00.0003130 since begin)

--After End

As you can see from the order in which the messages are printed, the function really is paused between loop iterations and resumed when the next value is requested by the loop.

This pausing and resuming can initially seem like magic, but below I will show how you can manually implement the same thing (albeit with a lot more code).

Manually Implementing IEnumerable

To manually implement the behavior above we need to build our own iterator that will keep track of state and produce one value at a time when they are requested. The C# interface for a collection that can be iterated over sequentially is IEnumerable<T>. A closely related interface, IEnumerator<T>, is the interface implemented by an object that holds the state for a particular iteration. I read an analogy for this that I really like in Jon Skeet’s book “C# In Depth (4th Edition)”. The analogy is to think of IEnumerable<T> as representing a book and IEnumerator<T> as representing a bookmark in the book. Many people can read the same book and use separate bookmarks to keep their place, but there is only one book. When talking about enumerating an array or list this analogy works very well.

For translating our yield return function into a manual implementation of IEnumerable<T> and IEnumerator<T>, the book analogy doesn’t fit as well. We don’t really have a “book” since the values are all generated on the fly. However, we still need to implement IEnumerable<T> if we want our object to be usable directly in foreach loops.

The following simple implementation of IEnumerable<T> can be used for our purposes:

class StateMachineEnumerable : IEnumerable<string>

{

int _first;

int _last;

public StateMachineEnumerable(int first, int last)

{

_first = first;

_last = last;

}

public IEnumerator<string> GetEnumerator()

{

return new StateMachineEnumerator(_first, _last);

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

This effectively just takes the two arguments that our YieldReturnDemo function takes, holds on to them in private fields, and passes them along to the constructor of StateMachineEnumerator (our IEnumerator<T> implementation).

You can mostly ignore the non-generic IEnumerable.GetEnumerator(), it is just a passthrough to the generic implementation. It is required due to IEnumerable<T> implementing IEnumerable which existed before generics were added to C#.

What State Needs To Be Preserved In Our IEnumerator<T>?

The more interesting part of manually implementing the equivalent of the YieldReturnDemo function is the IEnumerator<T> implementation. This is where we will manually keep track of the state between steps of the enumeration.

Let’s take another look at YieldReturnDemo and note the state that needs to be kept track of while the function is paused:

IEnumerable<string> YieldReturnDemo(int first, int last)

{

var beginTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

yield return $"begin";

for (var i = first; i <= last; i++)

{

yield return $"item {i}";

}

var endTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

yield return $"end ({(endTime-beginTime).Duration()} since begin)";

}

The following values need to be persisted across pauses (yield returns) in the method:

firstandlastbecause they are initialized before the firstyield return, and then used between each of the loopyield returns.beginTimebecause it is initialized at the beginning and is used again in the finalyield returnibecause the value needs to be maintained from one loop iteration to the next and we pause between each loop iteration due to theyield returnin the loop body.

Note that endTime does not need maintained across any pauses of the method because it is introduced after the yield return in the loop and is not used again after the following yield return.

Manually Implementing IEnumerator

The values that need to be maintained across pauses will become private fields in our IEnumerator<T> implementation. We will also need one other private field that keeps track of where within the method we are. We will write this method as a state machine within the IEnumerator<T> implementation and this final private field will be the state of the state machine.

Here is our IEnumerator<T> implementation commented with explanations of what is going on. Don’t worry if you don’t follow it fully. The main point is that it is a state machine and that this code is difficult and error prone to write by hand.

class StateMachineEnumerator : IEnumerator<string>

{

// State variable for our state machine

// (keeps track of what code to execute next)

int _state;

// State variables that need to be maintained between steps

int _first;

int _last;

private DateTime _beginTime;

private int _i;

public StateMachineEnumerator(int first, int last)

{

// Accept first and last arguments passed along from our

// IEnumerable<T> implementation

_first = first;

_last = last;

Reset();

}

// This is just for going back to the beginning of the

// iteration (not used by our foreach loop)

// It is used by our constructor to initialize these values

// though

public void Reset()

{

_state = 0;

// The state machine will re-initialize _beginTime

// and _i before they are used if started at _state=0

// so we don't really need to set them here

}

// Property that represents the current value of the

// iteration

public string Current { get; private set; }

object IEnumerator.Current => Current;

// Function that moves the iteration to the next step

// (sets `Current` to return the next value)

public bool MoveNext()

{

switch (_state)

{

case 0:

// Beginning of function to first yield return

_beginTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

Current = "begin";

_state = 1;

return true;

case 1:

// Loop initialization through first loop iteration

_i = _first;

if (_i > _last)

{

// Represents loop being skipped over

// due to _first being greater than last

EndState();

return true;

}

Current = $"item {_i}";

_state = 2;

return true;

case 2:

// Subsequent loop iterations

_i++;

if (_i > _last)

{

// Resumed to do next loop iteration,

// but loop exited

EndState();

return true;

}

Current = $"item {_i}";

return true;

default:

// no more values

return false;

}

}

private void EndState()

{

var endTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

Current = $"end ({(endTime-_beginTime).Duration()} since begin)";

_state = 3;

}

public void Dispose()

{

// We have nothing to dispose of

}

}

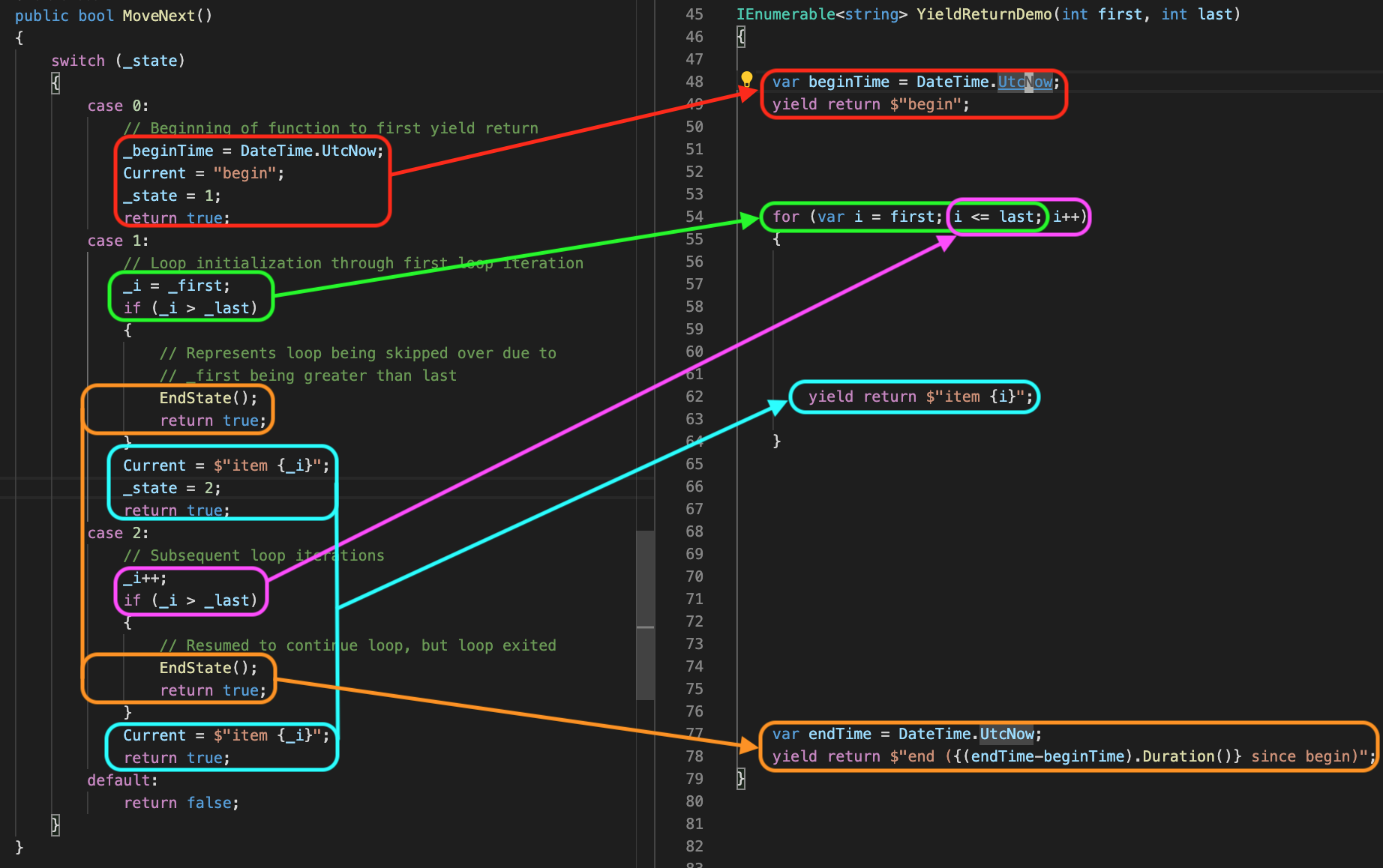

Below is an annotated image of the state machine code and the yield return code put side-by-side. The annotations highlight the parts of the code that are are used to implement the same behavior. As you can see the mapping is not one-to-one. I had to split up the loop logic and call the code that is equivalent to the last yield return from a couple of different places to get the right behavior. It may be possible to refactor this to clean it up a bit, but this accurately demonstrates the types of challenges that you’ll run into when trying to build this kind of thing without the help of yield return.

Conclusion

As you can see, it is possible to manually write code that is equivalent to a function using yield return, but it is complex and can be error-prone. Even in this relatively simple example, the readability advantage of yield return is dramatic. With yield return, the compiler effectively writes an equivalent state machine for you, and it can do it more efficiently.

If you are interested to read in more depth about the code the compiler generates and to understand how it handles things like exception handling and finally blocks, I would recommend reading Section 2.4 of the book “C# In Depth (Fourth Edition)” by Jon Skeet.

If you found this post interesting you may also like my post about C# generics.